- Complex fluids and materials

- Active condensed matter

- Liquid crystal physics

- Nonlinear elasticity

- Fluid-structure interaction

- Soft robotics

- Biological flows and biomedicine

- High performance computing

1.

Soft colloids

Microscopic soft particles are commonly found in nature and engineeringapplications. Examples include red blood cells, fluid vesicles and microgel particles. When placed in a liquid, soft particles can readily undergo large deformations to accommodate the hydrodynamic forces, which in turn has a significant impact on the macroscopic rheological properties of the mixture.

Microscopic soft particles are commonly found in nature and engineeringapplications. Examples include red blood cells, fluid vesicles and microgel particles. When placed in a liquid, soft particles can readily undergo large deformations to accommodate the hydrodynamic forces, which in turn has a significant impact on the macroscopic rheological properties of the mixture.

* Shear

rheology We consider a suspension of

elastic solid particles in a viscous liquid. The particles are assumed

to be neo-Hookean and

can undergo finite deformation. When placed in a shear flow, three

types of motion - steady-state,

trembling and tumbling - are found. The rheological properties

generally exhibit shear-thinning

behavior, and can even show negative intrinsic viscosity for

sufficiently soft particles.

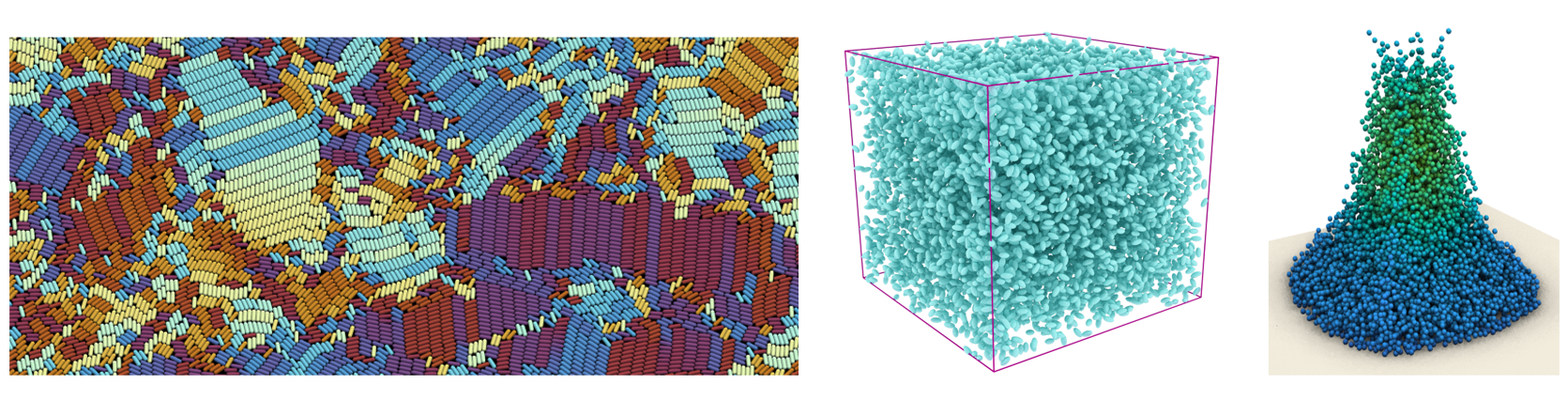

Fig 1: Suspension of deformable particles under simple shear

(

Gao et al. 2011).

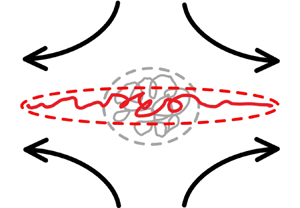

* Critical behaviors of polymer dynamics

We examine the underlying physical mechanisms of microdynamics of polymers when subjected to viscous fluid forces.

For example, we study the phenomenon of the ‘coil-stretch’ (C-S) transition, wherein a long-chain polymer

initially in a coiled state undergoes a sudden configuration change to become fully

stretched under steady elongational flows. We introduce a continuum model in this study to investigate the C-S transition in a

constant uniaxial elongational flow. Our approach involves approximating the unfolding

process of the polymer chain as an axisymmetric deformation of an elastic particle.

Fig 2: Coil-stretch transition of long-chain polymer (

Gao 2024

).

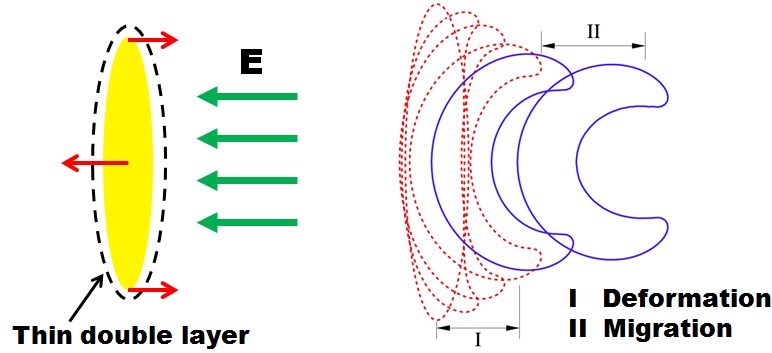

* Electrohydrodynamics We study the dynamics

of a long elastic particle

undergoing electrophoresis. The particle is elliptical in shape and is

initially aligned with its

major axis perpendicular to the direction of a uniformly applied

electric field. The particle tends

to curl up at its ends and arches in the middle. After a transient

deformation, the particle migrates

at Helmholtz-Smoluchowski velocity.

Fig 3: Electrophoresis of soft ellipsoidal particle (

T. Swaminathan et al. 2010

).

2. Active condensed matter

As a new branch of complex fluids, active matter is composed of self-driven constitutes with emergence of nonequilibrium physics. Despite the difference in composition, all these active systems orchestrate cooperative actions across various length and time scales, accompanying energy conversion from one form (e.g., chemical fuel) to another (e.g., mechanical work). Typical systems include cytoskeletal networks, synthetic microswimmers, bacterial suspensions, etc.

As a new branch of complex fluids, active matter is composed of self-driven constitutes with emergence of nonequilibrium physics. Despite the difference in composition, all these active systems orchestrate cooperative actions across various length and time scales, accompanying energy conversion from one form (e.g., chemical fuel) to another (e.g., mechanical work). Typical systems include cytoskeletal networks, synthetic microswimmers, bacterial suspensions, etc.

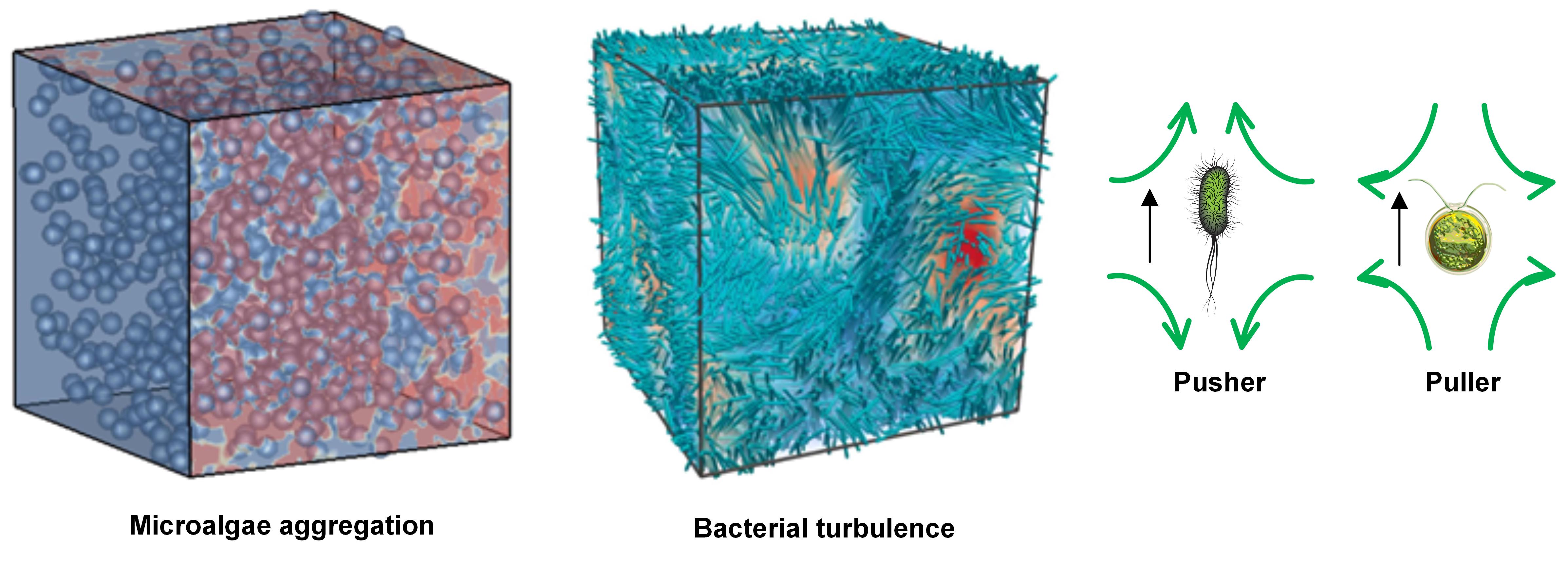

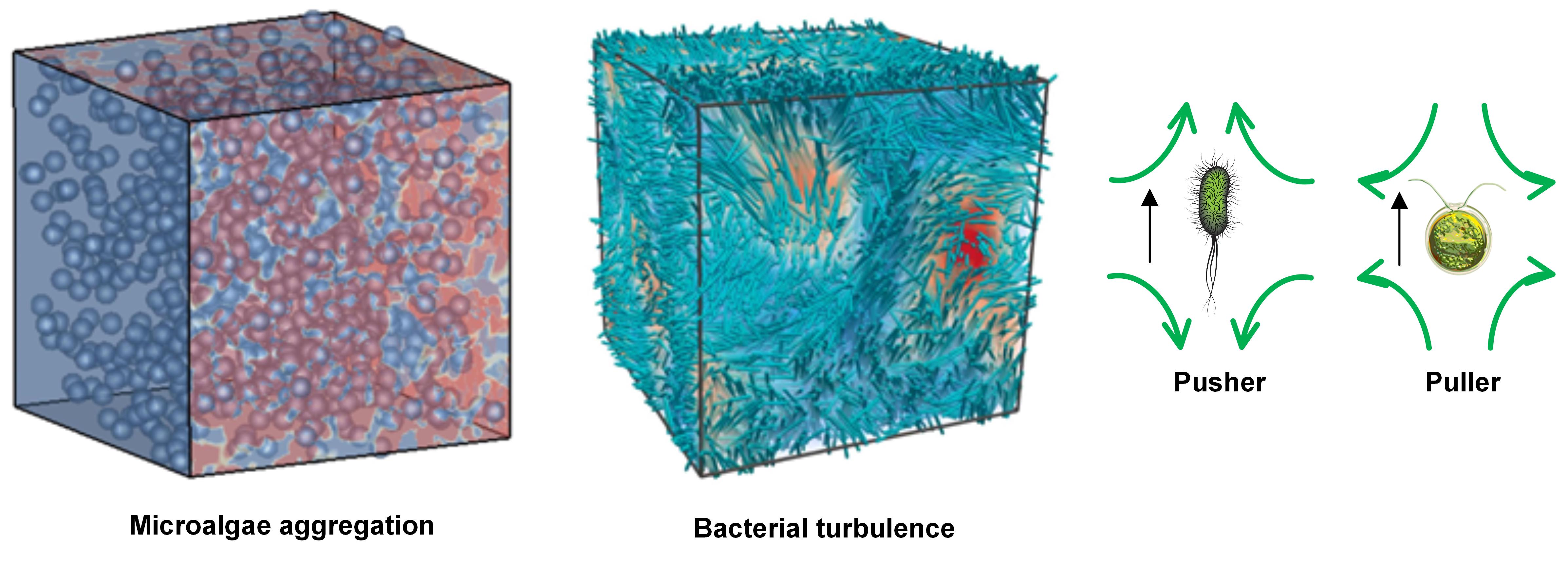

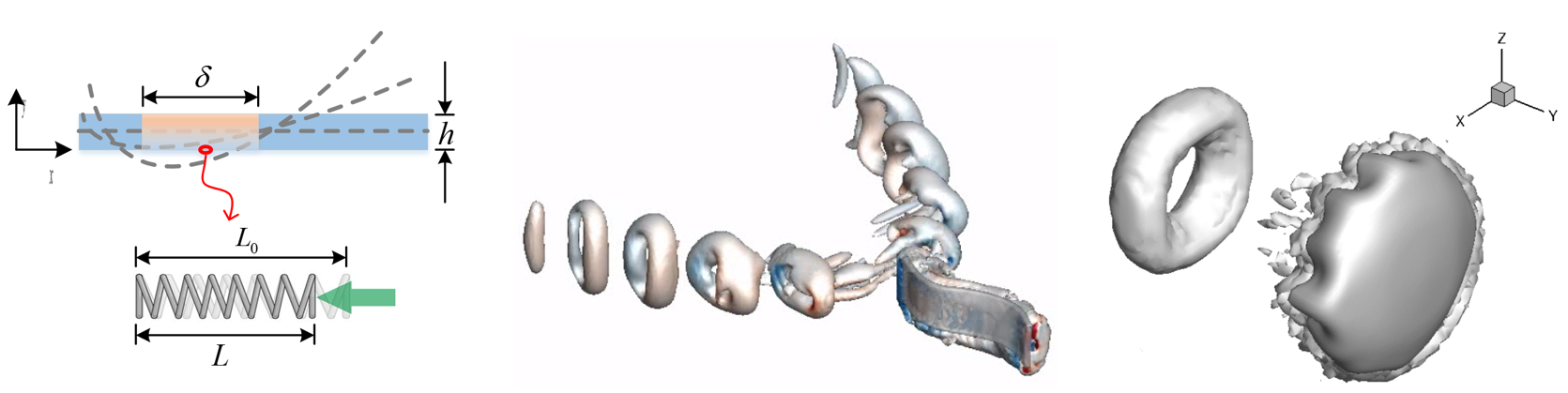

* Bacteria and algae

Active suspensions of swimming microorganisms, such as bacteria or algae, can exhibit fascinating collective behaviors that feature

large-scale coherent structures, enhanced mixing, ordering transition, and anomalous diffusion. Even in the limit of vanishing Reynolds

numbers, densely packed self-driven or swimming micro-particles effectively exert stresses upon the ambient liquid to act as a coupling

medium for the generation of active flows via instability concatenations to amplify the disturbances due to particle motions and local

(e.g., steric) interactions. We build a computation model, including the high-fidelity particle simulator and bottom-up continuum models,

to study the non-equilibrium physics of suspensions of rear- and front-actuated microswimmers, or respectively the so-called “pusher”

and “puller” particles. .

Fig 4: Direct particle simulations for spherical pullers (e.g., microalgae, (

Lin and Gao 2019

) and rod-like pushers (e.g., E. Coli).

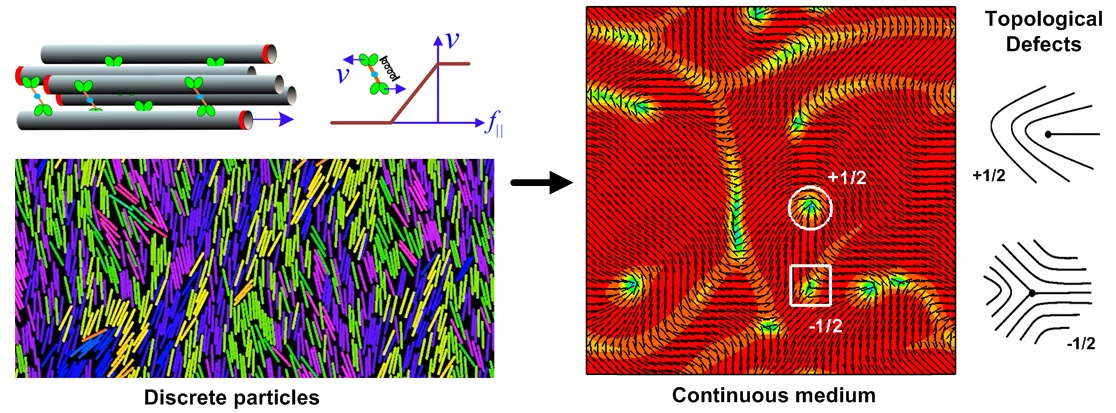

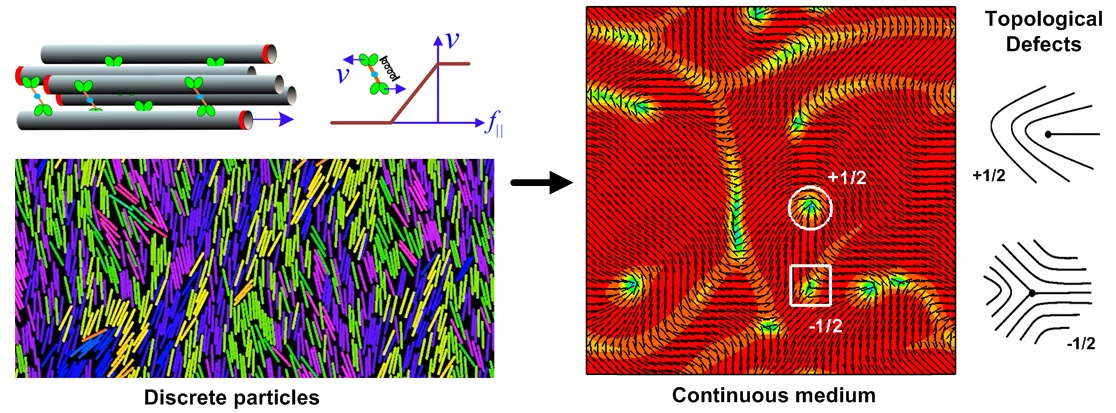

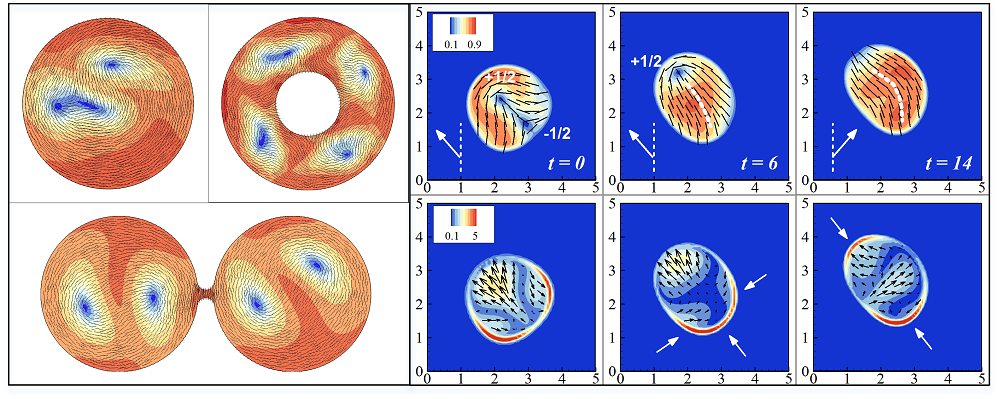

* Active cellular matter

Microtubules and

motor-proteins are the building blocks of

self-organized subcellular structures such as the mitotic spindle and

the centrosomal microtubule array. They are ingredients in new

"bioactive" liquid-crystalline fluids that are powered by ATP, and

driven out of equilibrium by motor-protein activity to display

complex flows and defect dynamics. We develop a multiscale

theory for such systems. Brownian dynamics simulations of polar

microtubule ensembles, driven by active crosslinks, are used to

study microscopic organization and the stresses created by

microtubule interactions. This identifies two polar-specific sources

of active destabilizing stress: polarity-sorting and crosslink

relaxation. We develop a Doi-Onsager theory that captures polarity

sorting, and the hydrodynamic flows generated by polar-specific

active stresses. In simulating experiments of active flows on

immersed surfaces, the model exhibits turbulent dynamics and

continuous generation and annihilation of disclination defects.

Analysis shows that the dynamics follows from two linear

instabilities, and gives characteristic length- and time-scales.

Fig 5: Multiscale analysis of motor-connected MT assemblies with hydrodynamics (

Gao et al. 2015

).

* Geometric control and manipulation

To effectively control the collective dynamics in various internally-driven systems, it is critical to manipulate the emergent

coherent structures. One way of doing this is to tune the suspension concentration and the amount of chemical fuels. Alternatively,

we can take advantage of the particle interactions, either individually or collectively, with obstacles and geometric boundaries to

manipulate the system more directly. By trapping active suspensions (such as Pusher swimmers or Quincke rollers) within the straight

and curved boundaries, stable flow patterns, such as unidirectional circulations, traveling waves, density shocks, and rotating vortices,

have already been constructed. More interestingly, active nematic flows under soft confinement by surface tension are able to generate

internal flows to break symmetry and drive the whole-body movement.

Fig 6: Generation of topological defects under the rigid (

Chen et al. 2018

) and soft (

Gao and Li 2017

) confinement.

3.

Soft robotics

Soft robotics is an emerging area that draws extensive interests from core areas in materials science and engineering, human health and medicine, applied mathematics, and biomechanics. It stimulates new structural design, and has advantages of simple control, light-weight, miniaturization, and affordable rapid fabrication. Compared to the conventional robots that are often made of rigid parts, the soft robots that are made from deformable materials can undergo flexible deformation under actuation, which essentially permits infinite degrees of freedom to facilitate complicated operations.

Soft robotics is an emerging area that draws extensive interests from core areas in materials science and engineering, human health and medicine, applied mathematics, and biomechanics. It stimulates new structural design, and has advantages of simple control, light-weight, miniaturization, and affordable rapid fabrication. Compared to the conventional robots that are often made of rigid parts, the soft robots that are made from deformable materials can undergo flexible deformation under actuation, which essentially permits infinite degrees of freedom to facilitate complicated operations.

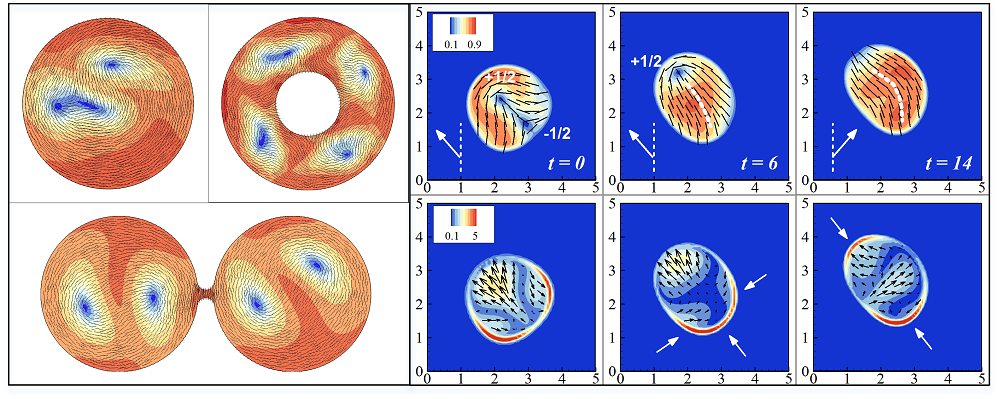

* Inertial swimmer

Designing soft swimming robots that actively deform in fluids is challenging. Fast swimming requires significant momentum exchange

between the robot and fluid to overcome viscous drag, demanding rapid, stable, and reversible deformations. Efficient locomotion

also depends on specific swimming gaits that exploit thrust from drag and wake effects—especially important at low or moderate Reynolds

numbers where viscosity dominates. Understanding these dynamics requires jointly analyzing robot geometry, material properties,

actuation strategies, and fluid interactions. Lightweight structures can also experience instabilities in fluid, complicating control.

Although many soft robots have been built and tested, fully understanding their propulsion still requires combining experiments with

accurate modeling and simulation.

Fig 7: Bioinspired design for soft swimming robots (fish and jellyfish,

Lin et al. 2019

) powered by active strain.

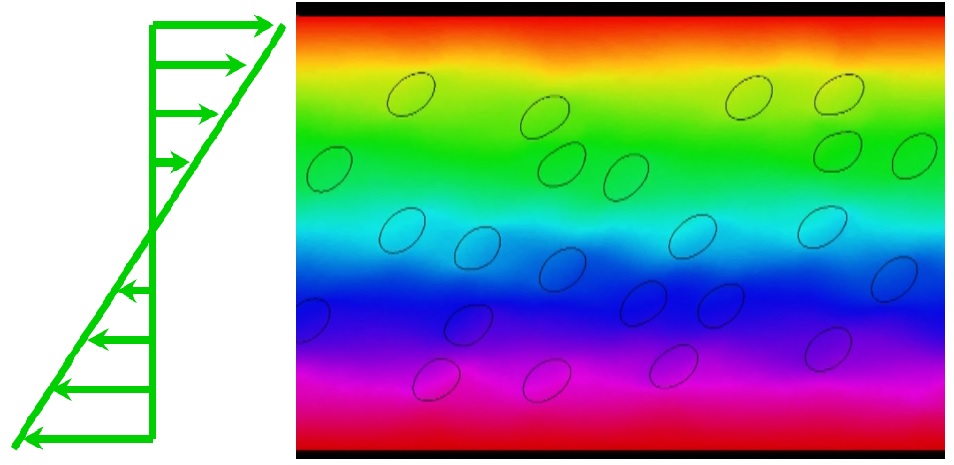

* Non-inertial swimmer and microfluidics

Many organisms live in microfluidic environments, either biological or synthetic, where

the fluid inertia is negligible. In the so-called Stokes (or creeping) flows, Purcell’s

scallop theorem explains that performing time-reversible motions cannot generate

directional swimming or locomotion owing to kinematic reversibility. We design a computational framework for

studying the undulatory motion of a finite-length biomedical robots, i.e., microrobots, in a solution of liquid

crystal polymers, a class of rigid, rodlike aromatic polymers that have much

larger sizes and higher aspect ratios than small molecules (e.g. para-azoxyanisole). Our numerical and theoretical studies suggests the

undulatory swimmers are in favor of aligning with the background nematic polymer structures.

Fig 8: Undulatory micro soft swimmers like spermatozoa prefer to align with the background polymer structures while navigating in anisotropic complex fluids

(

Lin et al. 2022

).

4.

Cardiac mechanics and patient specific model

The heart is a highly complex living structure whose primary function is to cyclically contract in order to generate a pressure gradient to perfuse all body organs including itself. To do so, however, the heart behaves an integrated system where all components of the operation, such as excitation contraction coupling, are tightly orchestrated. Heart failure often develops when one component fails or when the components are not operating synchronously. Computational modeling has been useful in developing understanding and generate hypothesis concerning the heart function, diseases and treatments. The recent advancement in HPC and patient specific models also include detail FSI between blood flow and the mechanics of the heart wall, which hence provide more accurate physical mechanisms for cardiac systems.

The heart is a highly complex living structure whose primary function is to cyclically contract in order to generate a pressure gradient to perfuse all body organs including itself. To do so, however, the heart behaves an integrated system where all components of the operation, such as excitation contraction coupling, are tightly orchestrated. Heart failure often develops when one component fails or when the components are not operating synchronously. Computational modeling has been useful in developing understanding and generate hypothesis concerning the heart function, diseases and treatments. The recent advancement in HPC and patient specific models also include detail FSI between blood flow and the mechanics of the heart wall, which hence provide more accurate physical mechanisms for cardiac systems.

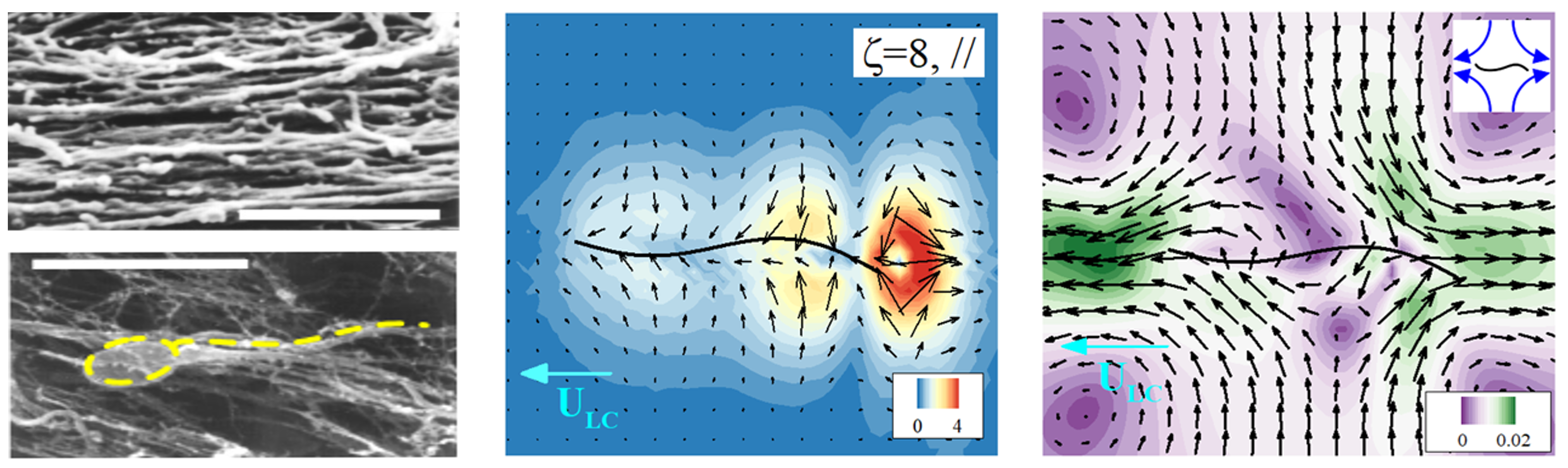

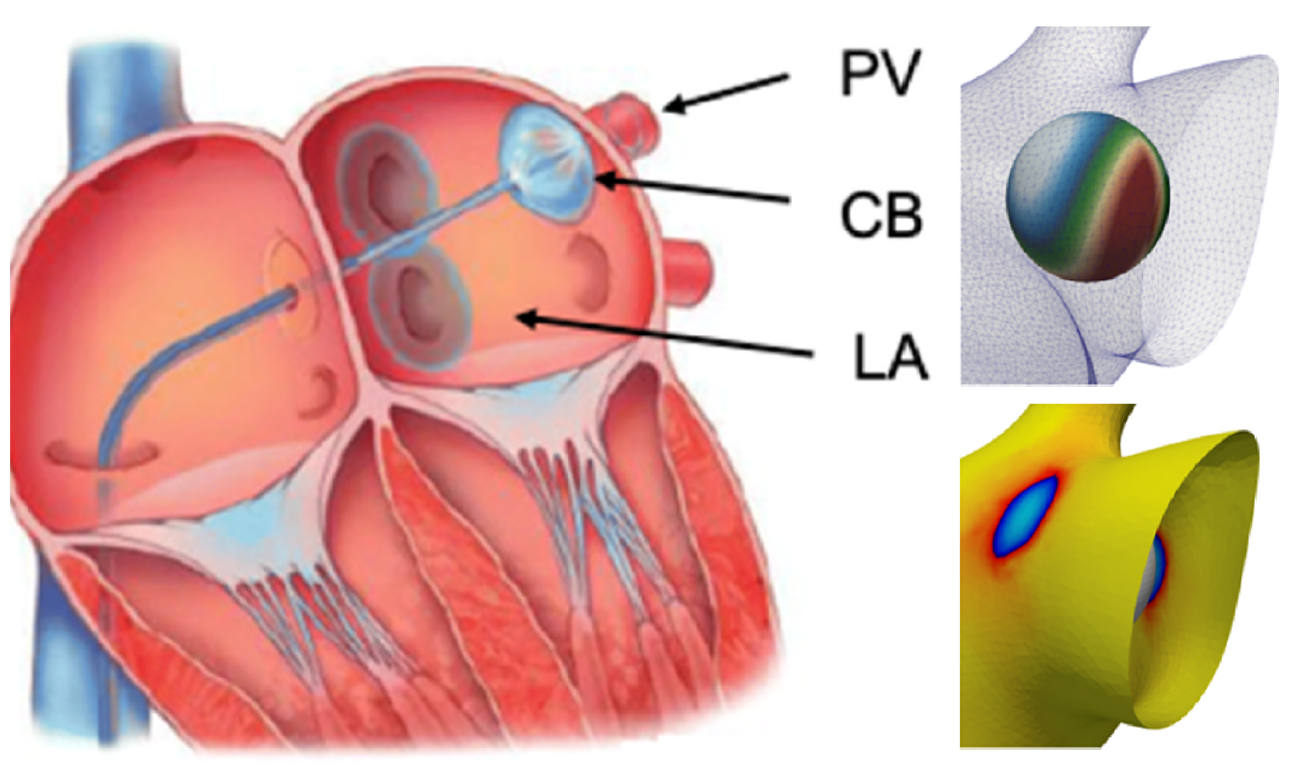

* Cryoballoon ablation

Cryoballoon ablation (CBA) is a cryo-energy based minimally invasive treatment procedure for patients suffering

from left atrial (LA) fibrillation. Although this technique has proved to be effective, it is prone to reoccurrences

and some serious thermal complications. We describe the development of a thermal-hemodynamics computational framework to simulate incomplete occlusion

in a patient-specific LA geometry during CBA. The modeling framework uses the finite element method to

predict hemodynamics, thermal distribution, and lesion formation during CBA.

Fig 9: Simulation of CBA in a patient-specific case

( Patel et al. 2023).

( Patel et al. 2023).